What is it?

Definition

Food insecurity is officially defined as a condition of a household where there are reports of change in quality or the desirability of diet or even reduced food intake during the year because of the lack of resources. Within Food Insecurity, there are the two categories of Low Food Security and Very Low Food Security. Low Food Security is indicated by reports of a disrupted eating pattern but with little or no change in the quantity of food consumed; while in Very Low Food Security, the household does not have enough food to keep everyone full (*1).

Today, 12.7% of households (15.8 million) are food insecure, and 12.9% of people (44.2 million) and 17.7% of children (13.1 million) live in a food-insecure household. 92% of people in the condition of low food security worry that food will run out. 83% reports that food bought “did not last”, and 78% cannot afford balanced meals. Unfortunately, these conditions are significantly aggravated among people with very low food security: almost all worry about food running out and are unable to afford balanced meals. 95% eat less than they feel should. The absence of access to food, especially nutritious food, and the accompanying anxiety are both defining characteristics of food insecurity (*2).

Figure 1 Data from Key statistics & Graphics

Data

An interesting aspect of food insecurity is the frequency in which a household experience such condition. On average and in total, food insecurity occurs in 7 months each year for a household. Among all the households categorized as food insecure at some point in five years, 51% of the households are insecure for only one year and merely 25% experience food insecurity for all five years. Statistics show that ¼ of the households with low food security and ⅓ of the households with very low food security experience the lack of resources chronically. This indicates that though there are many people who are food insecure, the majority are not in the situation constantly. However, the fact that families fall in and out of food security also means that the 12.7% of households seen each year is not everyone who has experienced food insecurity in the past and will experience food insecurity in the future. “A considerably larger number of households experience food insecurity at some time over a period of several years than in any single year,” says Economic Research Service (ERS) of the Department of Agriculture (USDA). The percentage of households without proper access to food right now might only be 12.7%, but the percentage of households at risk of falling into this category is inarguably higher, maybe even reaching 40 or 50%(*3). The point makes this an even more paramount issue (*4).

History and In Relation to Other Issues

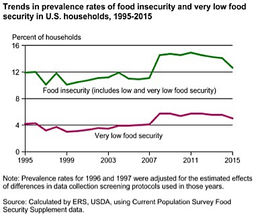

As can be seen from the chart, the food insecurity rate fluctuated (*5) considerably over the years. Comparing it to the national debt over the GDP and the unemployment rate, there seems to be a strong correlation, signifying the inseparability between the issue of hunger in America and the U.S. economy. The food insecurity rate increased substantially after 2008. Even though there is a total increase from 1995 to now, we are fortunately making continuous progress in the past years. The latest data of 12.7% was taken in 2015, a noticeable decrease from 14% of 2014 (*6).

Footnotes

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

*1 Definitions of Food Insecurity

*2 Key statistics & Graphics

*3 Just the author's estimation

*4 Frequency of Food Insecurity

*5 ERS explained that the seeming inconsistency of data from 1996 to 1999 might be caused by seasonal variation, as the census in odd-numbered years were done in April while the census of even-numbered years were done in August or September. Survey time was adjusted to early December since 2001.

*6 Key statistics & Graphics

*7 Ibid.

*8 refer to "A Public Survey" --> "Interesting Interview Quotes" for more information

*9 Laraia

*10 Ibid.

*11 Ibid.

*12 Food insecurity and Health Impacts

*13 Food insecurity is Associated

Figure 2, 3, and 4 Citation Inside

Some patterns can be found about which groups of people are more likely to lack access to nutrition. Though only 10.9% of households without children are food insecure, the number jumps to 16.6% for households with children. A staggering 30.3% of families led by single women are in need of food assistance. Race is a factor too: 19.1% of Hispanics and 21.5% of Blacks are food insecure, while 10% of Whites and people of other races fall into the category. Another aspect worth mentioning is the geographic locations: rates vary from 8.5% in North Dakota to 20.8% in Mississippi (*7).

Figure 5 Graph From Key statistics & Graphics

Because of the tight entanglement of all aspects of public policy, the problem of food insecurity cannot be resolved without addressing other issues related to it, such as unemployment, economic classes’ polarization, and unjust discrimination. In the San Francisco Bay Area, where this study was conducted, a strong association can be made with the increasing housing price. In an interview, a participant explained, “The housing here is so expensive, [...] and what are you going to do when you only have the money to pay another month of rent? You don’t eat.” (*8) One can see that the causes of food insecurity are extremely multifaceted and vary across regions and demographics. There are no definitive methods such as “Make more jobs!” or “Tax the rich!” to help improve the situation. This a very complex issue. On the other hand, the connectedness of food insecurity to other problems means that if this situation is resolved, improvements will be seen in many other areas too, increasing the importance of food security as a subject of public policy.

Health and Why We Should Help

As mentioned above, food insecurity is an essential part of a web of issues in today’s society; therefore, effort invested in this area not only brings the ones in need happiness but also alleviates other struggles. Furthermore, an unavailability of food is not merely an inconvenience but has serious health effects.

Food insecurity has been found to link to chronic diseases, particularly type 2 diabetes. Scientists theorized that food insecurity promotes chronic diseases through both diet and stress. When one lacks money for food, the best, and sometimes the only, solution is “cheap, palatable food that is dense in carbohydrate and fat.” Further exacerbated by the “cyclical nature” of unbalanced intake of food in the beginning of the month versus the end of the month, food insecurity can cause weight gain in a short period of time. Stress caused by economic struggles also promotes visceral fat accumulation; therefore, it contributes to the chronic diseases. Under severe anxiety, the body releases hormones such as cortisol that prompts people to consume highly energy-dense food and adjust metabolism. Just like how individuals turn to “comfort food” high in sugar and fat during emotionally stressful times, victims of food insecurity are more likely to have an unbalanced diet than their food-secure counterparts. (*9)

Food insecurity is also associated with an inadequate intake of fruits and vegetables. According to a study done in Toronto, Canada, women of Very Low Food Security households consume less than 85% of vitamin A, folate, iron, and magnesium than needed. This 15% difference is “used to indicate a sufficient reduction in essential nutrients that may put women at risk of nutrient deficiencies.” (*10)

All the consequences above are serious enough for lacking food to be a paramount issue. Yet, the health effects are amplified for children. Food insecurity during one’s critical growth periods increases one’s risk of developing chronic diseases and metabolic syndrome by activating the stress response (*11). Connections were also made to a higher likelihood of getting hospitalized, anemia and asthma, behavioral problems at school, and even depression (*12). Another study, conducted to gain insights on young children's health, interviewed the caregiver of 11,539 individuals younger than 3 and found that food-insecure children are almost twice as likely to be in “fair or poor” health than their food-secure counterparts. Though interestingly, when the sample space is restricted to only food-insecure households that receive food stamps, the correlation, though not completed eliminated, reduces by much (*13). A reasonable interpretation of this evidence is that it is not the absence of wealth that causes the health conditions; rather, it is the insufficiency of nutrients. As a result, food assistance programs do great benefits. They not only help the ones in need but reduce the nation’s health bill as a whole.